Nicola Pryce: Searching For The Voice Of Opium Addiction In 1796

15 May 2019

Today on the blog, we welcome Nicola Pryce, author of historical fiction set in Cornwall. Her fourth novel, The Cornish Lady, was published in March this year. She told us about how she researched opium addiction in the late eighteenth century to bring her character to life.

Today on the blog, we welcome Nicola Pryce, author of historical fiction set in Cornwall. Her fourth novel, The Cornish Lady, was published in March this year. She told us about how she researched opium addiction in the late eighteenth century to bring her character to life.

Laudanum (opium mixed with alcohol) was readily available as a painkiller for those with means – it wasn’t until the 1800’s that patent medicines using opium preparations, such as Dove’s Powder were readily available, without restriction, to the poorer classes – but opium in its raw state was becoming increasingly available in I796, and the docks of Truro and Falmouth had their fair share of sailors bringing it back from their travels to sell in the opium dens that sprang up on the quaysides.

I had long had the image in my mind of the aristocratic Lady Bertram from Jane Austin’s Mansfield Park dozing on the chaise longue with her vial of laudanum, but to convincingly portray my heroine’s brother, a young man with an opium addiction, I wanted to find a first-hand account written in the last decade of the eighteenth century. My first thoughts turned to Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

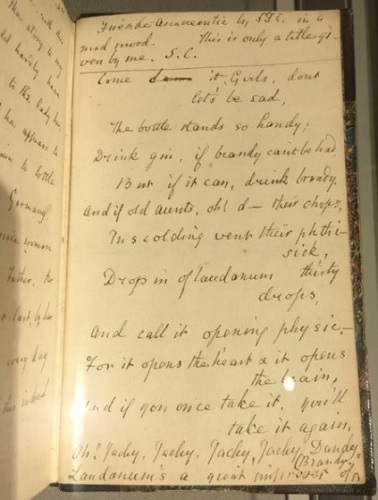

In 1796 Coleridge was living in a cottage in Nether Stowey, a short drive from where I live in Somerset, and I was thrilled to find a poem in his notebook. Not so much a poem, but a light-hearted ditty, which rings with exuberance, even mischief. Putting opium into his old Aunts’ brandy to stop them from scolding isn’t irresponsible, it’s just a bit of fun; a young man’s idea of a prank.

Come damn it, Girls, don’t let’s be sad,

The bottle stands so handy:

Drink gin, if brandy can’t be had

But if it can, drink brandy.

And if old aunts, oh ! d – their chops,

In scolding vent their phthisick,

Drop in of Laudanum thirty drops,

And call it opening physic –

For it opens the heart and it opens the brain,

And if you once take it, you’ll take it again,

Oh! “Jacky, Jacky, Jacky, Jacky Dandy

Laudanum’s a great improver of Brandy.”

The voice of my character, Edgar Lilly, was beginning to emerge, but on further research my second source, Confessions of an English Opium-Eater by Thomas de Quincy, quickly dispelled this sense of exuberance. It made for chilling reading, exactly mirroring the jeopardy and fear I wanted to portray in my book. Published in 1821, it chronicles de Quincy’s laudanum addiction which started in 1804 and spiralled out of control – all because of his facial neuralgia, the ‘coercion of the severest pain’.

The voice of my character, Edgar Lilly, was beginning to emerge, but on further research my second source, Confessions of an English Opium-Eater by Thomas de Quincy, quickly dispelled this sense of exuberance. It made for chilling reading, exactly mirroring the jeopardy and fear I wanted to portray in my book. Published in 1821, it chronicles de Quincy’s laudanum addiction which started in 1804 and spiralled out of control – all because of his facial neuralgia, the ‘coercion of the severest pain’.

Combining these two texts, Edgar Lilly started to become real. As with de Quincey, childhood influences would play their part – the death of his mother at an early age, a prosperous Father determined to see his family rise in society. Boarding school, and a place at Oxford. A lonely youth struggling academically, caught between the different strata of society, taunted as ‘trade’ as he walked the corridors of his college – ‘Old Smelter Boy’s father, trying to buy him some class’.

A youth who sought solace from the agony of toothache, who found he could distant himself from his fears and be cradled in ‘velvet arms’. His early sense of exuberance, his witty retorts, his confidence, his sense of a prank, quickly overtaken by jeopardy and malice.

Edgar Lilly’s voice suddenly became clear. It was raw, it was lonely; it was full of pain and self-loathing. I could hear his cry for help – the cry of a vulnerable boy in the clutches of an unscrupulous man.

That’s so interesting – it shows how much work goes into researching historical fiction, and how much your work benefits from it as it makes the characters all that more real.

So onto the interview…

So onto the interview…

Your novels are set in Cornwall – what is it about the county that draws you, and your readers, in?

Definitely my early reading – often under the bedcovers by torchlight in my boarding school. My parents lived in Rome and I was brought up as a city girl, but any book about Cornwall drew me so completely: Daphne Du Maurier, Winston Graham, I devoured everything I could, breathing in the sea air, walking the cliffs, running up the steep alleys to escape the press gang. As far as I was concerned the men were dark, handsome, and rugged and I couldn’t wait to get there.

When I did, I was in my mid-thirties, had three young children, and was married to a sailor. My first glimpse of Cornwall was sailing into Fowey and every expectation was met – the sense of place, of history, the extraordinary beauty; the ruggedness of the landscape, the hardship, the force of the winds lashing the coast and whistling across the moor. But it is also the pride the Cornish people have for their traditions, their industrial heritage, their crafts and food, their sense of where they belong that draws me every bit as much as the atmospheric harbours with their narrow alleys and the flower-strewn cliffs with their secret coves.

For the last twenty five years we have sailed in and out of the timeless harbours of the south coast of Cornwall and my stories are based in the areas I now know so well. I’m no longer the child desperate to escape the confines of a strict boarding school and city pavements, but I’m breathing the salt air, walking the cliff paths, if not exactly escaping the press gang. It’s a huge privilege, and one I want to capture in my books for others to enjoy.

Some of the characters in your historical novels have disabilities – are there any particular challenges in researching and depicting disability in the past? Did you unearth anything unexpected?

There’s quite a bit written about disability in the eighteenth century, including David M. Turner’s book, Disability in Eighteenth-Century England: Imagining Physical Impairment (Routledge Studies in Modern British History) but I failed to find a novel written around 1796 which depicted a character with disabilities. (Do, please, tell me if I’ve missed one.) The unwitting testimony of how a person with disabilities was portrayed in literature, at that time, would be interesting.

According to historicengland.org.uk, at the end of the 18th century, out of a population of nine million, probably fewer than 10,000 disabled people lived in an institution. Instead, they lived in their communities, supporting themselves in any way they could. Some were sent to stay with families in the country, like Jane Austen’s older brother George and her uncle Thomas, while others were taken in by grand estates and worked as gardeners or in the laundry.

There’s plenty of evidence for the stereotypical village idiot leaning against the gate in a smock, and I think that’s the most difficult thing about depicting a person with disabilities in the past. Our sensibility recoils from the mockery, and the words idiot, cripple, lunatic and simple sound horrific to modern ears, as do the depictions in the cartoons of that period, and the parade of dwarfs and hairy women in the travelling circuses of that time.

In London, the Foundling Hospital taught blind orphans to play the violin so they could beg on the streets; there were famous deaf artists earning a good living and prints painted of blind women selling flowers. But in Cornwall, life was tough enough if you weren’t wealthy – take away the means to do physical work, or a follow a trade, and you faced a real struggle.

In 1818 St Lawrence’s Hospital in Bodmin was designed to ‘deal’ with the insane poor and mirrored the new trend of institutions for lunatics which grew throughout the 19th century, but at the end of the 18th century, most were only locked up if they were deemed a threat to the safety of others. The majority of people with disabilities were looked after by family and community.

Education was limited even to the able-bodied, but to be a deaf mute? Or blind? In the harsh and often brutal conditions of Cornwall, it must have caused great hardship.

In Pengelly’s Daughter and The Cornish Lady, I have two characters, the first with learning difficulties, the second, unable to hear or speak. As vulnerable men, I wanted to portray the jeopardy they faced, how they could so easily fall victim to bullies, and how uncertain their futures would be without the support of those with means.

But what language to use? Fight shy of terms that horrify modern readers, or use the words of the time? I decided to use the words I find so distasteful, but sparingly, and at the same time making it explicit that each of the men had dignity, natural charm, and were loved for themselves – for who they were, and for what they gave back to their employers who took them under their wings.

‘A deaf mute child, the same age as the heir to Trenwyn House, washed on to their beach in a laundry basket, Lady Clarisa scooping him out of the water without a second thought, giving him to her childless gardener to nurture and love. The child’s mother must have known just when and where to float that basket, but she would never have guessed her imbecile child would end up growing herbs for every apothecary and physician in Cornwall.’ from The Cornish Lady.

Did I unearth anything unexpected? Yes. While researching spectacles for my seamstresses and my hero in The Cornish Lady, I was fascinated to discover that split lenses were produced by London opticians as early as 1760, that frames came in leather, horn, silver, tortoise-shell or steel and that the Venetians were wearing green tinted sun glasses to protect them from the sun on the lagoon. All these facts, I have used in my books.

You’re giving a talk at Ilminster Literary Festival in June – have you given a talk before and what tips would you give to other writers about appearing at a literary festival?

You’re giving a talk at Ilminster Literary Festival in June – have you given a talk before and what tips would you give to other writers about appearing at a literary festival?

I talked about The Cornish Dressmaker at the Yeovil Literary Festival last October which I thoroughly enjoyed. I think my main advice would be to get there early to check the IT links, so you know everything is connected and working – like the sound on videos, etc. Also, wear something you feel good in, and have some water handy.

I illustrated my talk at Yeovil with ten photos on Powerpoint from my laptop, and I’m doing the same for Ilminster in June. I began, briefly, with my journey to publication, followed by an illustrated talk on the history behind my book, then three short readings, ending with a very lively question and answer session.

All the way through, I kept glimpsing the clock, trying not to spend too long on one part. I suppose timing comes with experience, but what I will do again, which I did at Yeovil, is to greet people at the door as they come in. It made it much easier to stand and face everyone after exchanging a few words with them.

I have A3 posters for each of my book covers and I took a supply of bookmarks which all disappeared. All in all, it went very quickly, and I think it’s important to check how long you’ve been given to sign books afterwards. It took much longer than I thought it would.

My advice? Do it, even if you feel nervous.

About the author: Nicola Pryce trained as a nurse at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London and followed a fulfilling career before the itch of writing got to her. She loves both literature and history and has an Open University degree in Humanities. A qualified adult literacy support volunteer, Nicola lives with her husband in the Blackdown Hills in Somerset. She and her husband love sailing and together they sail the south coast of Cornwall in search of adventure. If she’s not writing or gardening, you’ll find her scrubbing the decks.

Nicola is a member of the Romantic Novelists’ Association and The Historical Writers Association.

Find out more at Nicola’s website and follow her on Facebook, Twitter and Pinterest.

The Cornish Lady is available in paperback, ebook and audiobook from Amazon, Kobo, Waterstones, WHSmith, etc.

About the interviewer: Eleanor Harkstead is from the south-east of England and now lives somewhere in the Midlands with a large ginger cat who resembles a Viking. Her m/m romantic fiction, co-written with Catherine Curzon, spans WW1 to the present day and is published by Pride. The Ghost Garden, the first installment in historical paranormal series The de Chastelaine Chronicles is out now, published by Totally Bound. You can hear Catherine and Eleanor chat about writing on their Gin & Gentlemen podcast. Find out more about Eleanor at curzonharkstead.co.uk, and follow her on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

About the interviewer: Eleanor Harkstead is from the south-east of England and now lives somewhere in the Midlands with a large ginger cat who resembles a Viking. Her m/m romantic fiction, co-written with Catherine Curzon, spans WW1 to the present day and is published by Pride. The Ghost Garden, the first installment in historical paranormal series The de Chastelaine Chronicles is out now, published by Totally Bound. You can hear Catherine and Eleanor chat about writing on their Gin & Gentlemen podcast. Find out more about Eleanor at curzonharkstead.co.uk, and follow her on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.